History and heritaged heritage

History

Route 24 of the Itinerary of Antonino during the Roman domination. The Balat Humayd path of the Muslims. The “carriage road” built by the Catholic Monarchs. Camino Real, the paved road (N-VI) of Fernando VI in 1750, commemorated in the monument that crowns the Puerto del León. Even the tunnels on the motorway that today cross the Sierra de Guadarrama through our town speak of the importance of Guadarrama as a passage between the two plateaus, and how the coming and going of travellers has enriched our heritage and culture.

A privileged location historically. A rich and varied natural environment that makes Guadarrama an attractive location that is well worth a visit.

The name Guadarrama (wadi-l-ramal, river of sand) comes from the Arabic language. However, its origin as a town must be sought in the processes of reconquest from the Muslims in the eleventh century and repopulation of the twelfth century. The conquest of Toledo by Alfonso VI in 1085 moved the frontier to the Tagus River. Thus began the repopulation and feudalization of the territory delimited by the Duero and the Guadalquivir. The monarchs, faced with the need to repopulate the conquered lands, granted municipal charters to populate the Extremadura around the Duero river and the Transierra. Guadarrama has always been a place of passage and this could be the origin of its foundation by the natives of Segovia as a stable settlement around 1268 under the reign of Alfonso X the Wise.

The conflicts between the Segovia and Madrid councils over the dominion of these lands ended when Alfonso X incorporated this disputed territory into the crown of Castile, and it became known as the “Real de Manzanares”. In the 14th century Juan I donated it to the Mendoza family, and it became a definitive estate when Juan II in 1436 granted the Mendoza family full dominion over these lands.

Guadarrama was therefore one of the places belonging to the Real de Manzanares under the jurisdiction of the town of Manzanares. The concession of the privilege of “villazgo” to Guadarrama in 1504 marked an important milestone in the history of the municipality. From this time on Guadarrama had its own municipal organization and autonomy from Manzanares in matters of justice and jurisdiction. However, this does not mean that it was outside the jurisdiction of the Duke of Infantado. It continued to form part of the ducal domains, as can be seen from the answers given by the inhabitants to the Ensenada Cadastre in 1751.

The situation of Guadarrama as a crossroads has marked its history.

Balat Humayd, the old path opened in Muslim times that crossed the Sierra de Guadarrama, continued to be used in medieval times. The increase in traffic meant that from the middle of the 14th century the network of roads was extended and improved to allow road traffic (until then traffic was done on the backs of animals). The Catholic Monarchs began the task of building and repairing these roads. The most travelled road linking the two plateaus was the so-called “camino de los carros”, or carriage road, which passed through the Guadarrama pass. The movement of goods was taxed from this moment with the payment of a fee, as was the carrier. The rights to charge tolls in Guadarrama was granted to Pedro González de Mendoza in 1383 and was collected by the Casa de Mendoza until the end of the Ancient Regime. This link to the road benefited the locals, whose economic activity was linked to the portage with its carts carrying wood, coal and wheat.

In the 17th century the mountain range was still crossed indistinctly by either La Fuenfría or Tablada. It was in the 18th century when the modernisation of the Spanish roads promoted by Fernando VI and Carlos III took place. Guadarrama benefited from this and in 1749 the old carriage road became a new paved road that followed the layout of today’s Nacional VI. In 1750, to commemorate the culmination of the ascent of the pass, the monument known as “el alto del león” was erected. This symbol is the one used by the Town Hall in its municipal seal.

Again the privileged situation of Guadarrama was related to the construction in this century of the Panera Real (current church of San Miguel Arcángel) and the Molino del Rey to supply Madrid. Its execution was financed by the Real Pósito de la Villa y Corte de Madrid.

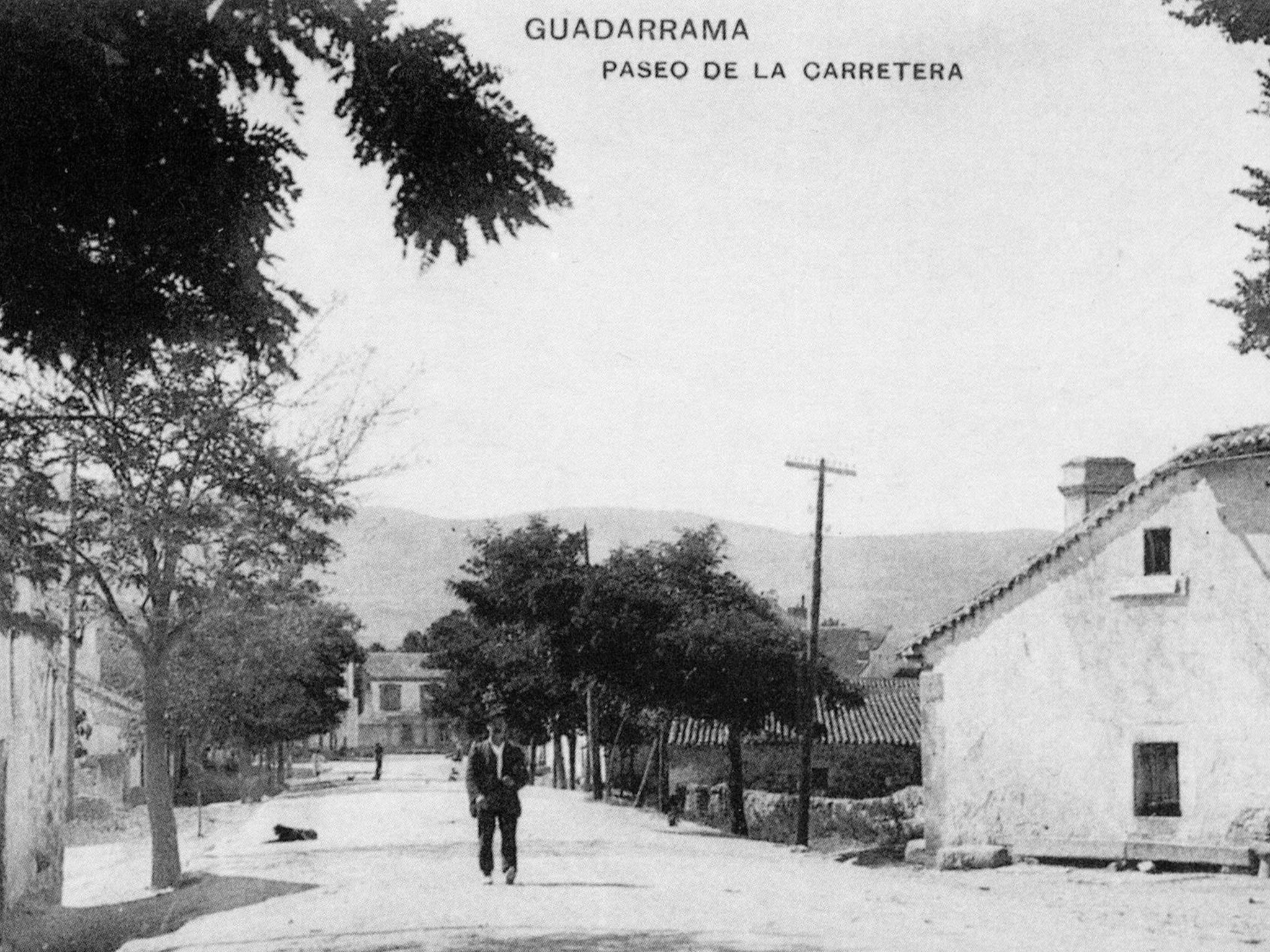

The construction of the new road influenced the urban layout of the town. Until that time the bulk of the town was on the right side of the road or Calle Real, but an important focus of urban life began to develop on the left side of the road between the Plaza de las Cinco Calles and the Plaza de la Fuente.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Guadarrama mountain range began to receive the first hikers and health establishments were built. The springs of La Porqueriza and La Alameda, around which the first spa colonies began to be built, took on greater importance and attracted the Madrid bourgeoisie, and the first country houses or chalets, as they were known in the area, began to proliferate.

During the Civil War from 1936 to 1939, Guadarrama suffered almost complete destruction and a marked loss of population. It was therefore one of the towns chosen for reconstruction by the General Directorate for Devastated Regions. All this reconstruction once again led to the dynamization of urban and commercial life around the axis of the N-VI road.

The urban structure changed at the end of the 1960s with the proliferation of apartment blocks thanks to the attractiveness of the mountains to visitors.

Today the declaration of the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park has opened new perspectives for the present and the immediate future of Guadarrama.

Heritage

The passage of history and the people who have inhabited this place have left a rich heritage. Among its noteworthy monuments and buildings are:

Parish Church of San Miguel Arcángel:

Before being a church, this place was the old Pósito or Panera Real. At the end of the war with the French, a private individual acquired the remains and donated them for the construction of a new church for the village, but only one part was rebuilt as the home of the parish priest. It underwent several renovations during the 19th century and during the Civil War it lost its roof, which was rebuilt by the Directorate General for Devastated Regions.

Los Caños Fountain:

In order to beautify the Camino Real de Castilla and supply water to the people and travellers crossing the mountains, in 1785 King Charles III ordered the construction of the fountain of Los Caños. This elegant neoclassical fountain became a focus of attraction and expansion of the town’s buildings, on the fringe of the central nucleus around La Torre.

Town hall and Plaza Mayor:

The Town Hall is structured around a square conceived as the five sides of a regular octagon. It is located very close to the site occupied by the old Town Hall destroyed during the Civil War. It belongs to the group of buildings built by the General Directorate for Devastated Regions in the 1940s during the reconstruction of Guadarrama.

Rosario Bridge:

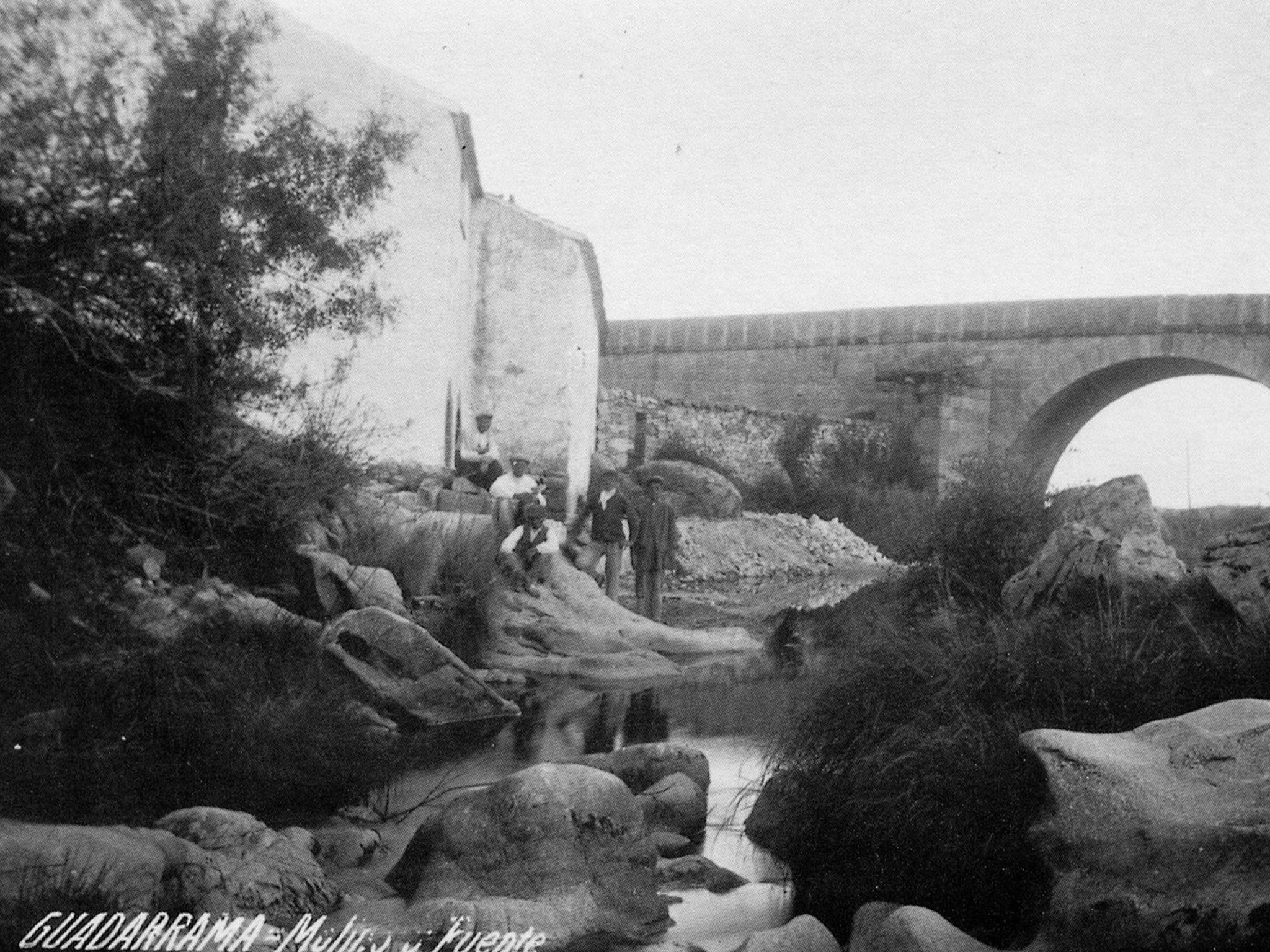

Built in the 18th century during the reign of Charles III, it is located at the exit of the town on one of the transverse communication axis, the Camino Viejo de El Escorial. It owes its name to one of the two shrines in the vicinity. Together with the Herreño and the Retamar bridges, it forms part of an interesting group of structures associated with the old paths, created to cross the middle course of the River Guadarrama. The current use of the three bridges shows the quality of these works of Bourbon engineering.

La Torre Cultural Centre:

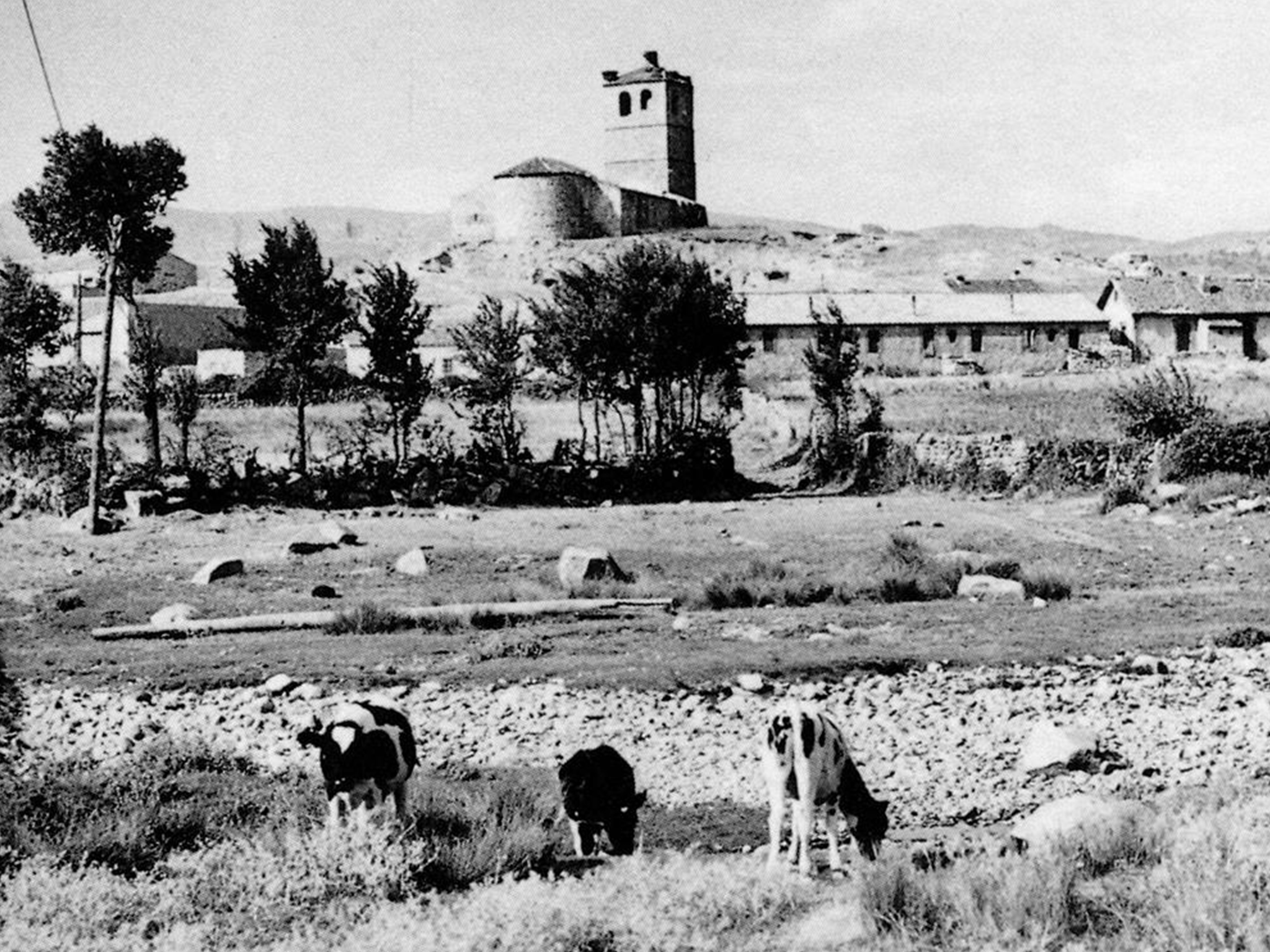

Located on the hill on which the town was originally established, it was the church of San Miguel Arcángel until the end of the 19th century when its functions were moved to the building of the old Paneras Reales. The church, originally Romanesque in style, has undergone many renovations throughout its history. The existence in its structure of remains that are believed to be Roman and Arab suggests the possibility of settlements of these peoples in the surroundings. The Mudejar apse with its masonry and brick walls, the wall and the tower dating from the Middle Ages are preserved.

Due to its strategic location, from which a large part of the surroundings can be seen, it was used by the Napoleonic troops as a barrack during the French invasion. After the Civil War, the atrium was used as a dwelling by several families in the municipality. Today it is a cultural centre.

Guided tours of La Torre Cultural Centre can be arranged with the tourist services of the Town Hall. On clear days you can enjoy privileged views of the surrounding mountains. The guided tour is completed with interpretative panels on the main historical milestones of the municipality.

Neighbourhood of Devastated Regions::

Given its strategic geographical location, Guadarrama suffered the destruction of most of the municipality’s buildings at the end of the Civil War. During the 1940s, the General Directorate for Devastated Regions undertook the remodelling of the urban nucleus, such as the town hall and the construction of this neighbourhood.

Different types of residential buildings can be observed. All of them are covered with Arabic tiles on masonry walls and granite masonry. Sometimes the houses were built with agricultural outbuildings. The layout of the district covers five blocks articulated by four longitudinal streets and a series of short cross streets. The limits of the district are the Calle de la Sierra to the north and the Calle de la Calzada, the site of the singular buildings of what was the School Group, today the Hogar del Pensionista.

The entire façade of Calle de la Sierra is an example of the old day labourers’ dwellings. In Calle Alto de los Leones de Castilla, there are alternating houses for day labourers and livestock farmers. In the blocks located to the south of the street the houses were for cattle ranchers. The site is completed with the singular buildings on the corners of the blocks.

Paseo de la Alameda:

The Colonia de la Alameda emerged in the 1920s as a group of summer houses around the La Alameda spa-hotel, opened in 1902 in the place now occupied by the Residencia de Mayores Virgen de la Cabeza. The fame of its waters for consumption and bathing, the excellent service in the hotel and the quality of its restaurant made it a meeting point for the Madrid bourgeoisie.

After the Civil War, both the colony and the spa had to be rebuilt. The spa became a children’s preventorium in 1946. Three models of houses were built in the colony: the neo-Mudejar style houses, the mountain style houses imitating traditional constructions and the houses finished in exposed or plastered stone.

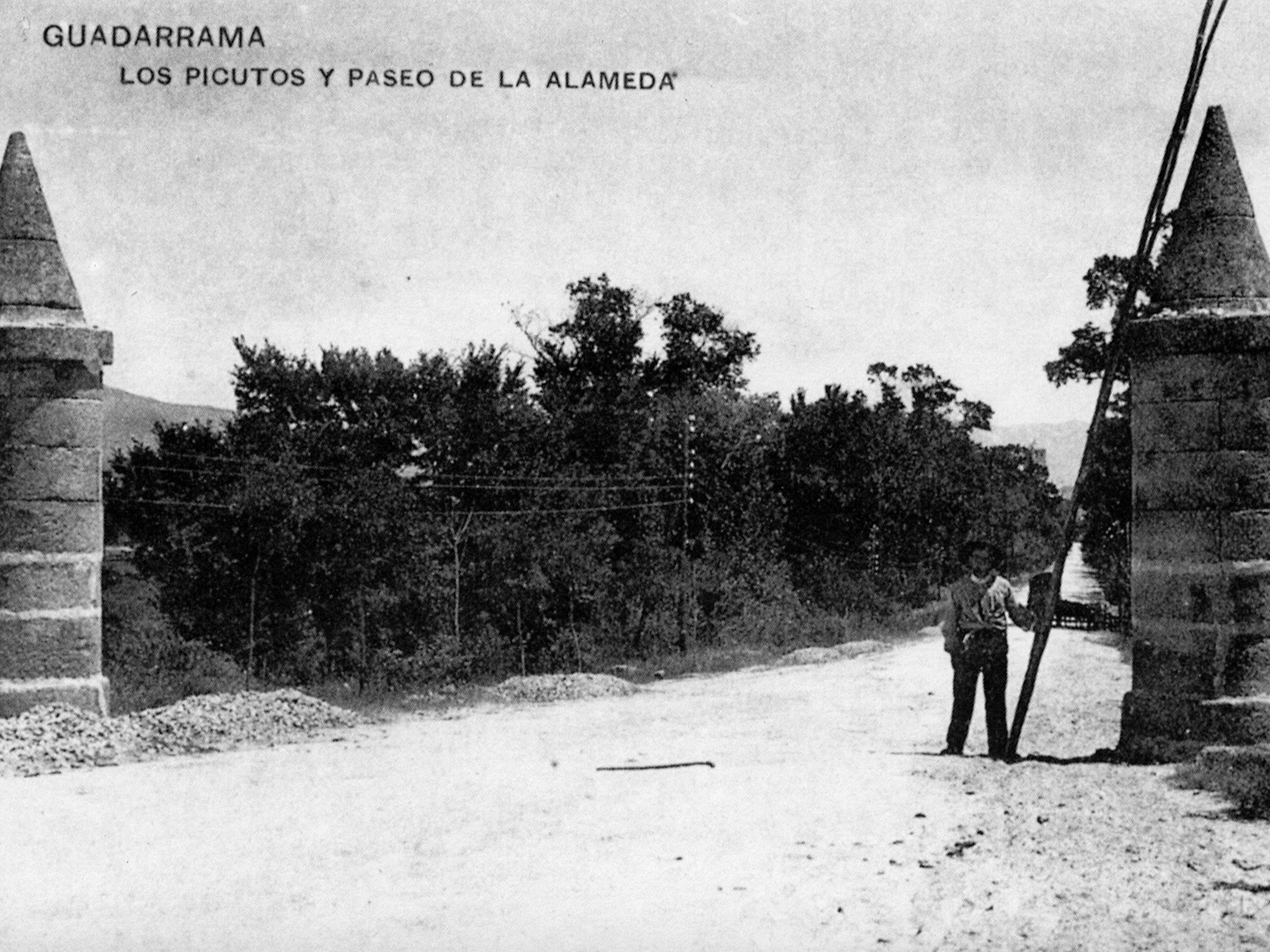

The Picutos are two stone cylinders crowned by cones. They are located on both sides of the pass (Guadarrama and El Espinar) and on both sides of the road. These landmarks are part of the Camino Real de Castilla. Their original purpose was to mark the path and, if necessary, to close it in the case of snowfalls, or to control the passage of carts loaded with firewood or other goods, especially at night.

El Aralar house is one of the most unique ones on the Paseo de la Alameda. It used to be a private house and today, after a thorough refurbishment, it has become the Casa de la Juventud de Guadarrama (Guadarrama Youth House). It was built in 1935 and destroyed during the Civil War. After its reconstruction it was abandoned in the 1980s until its current recovery. Its architecture is in the alpine style, with a rectangular floor and a very pronounced gabled roof.

La Casa del Peón Caminero is a 19th-century mansion with a large plot of land located at the beginning of the road to the Guadarrama pass. The most striking feature of the house is the large coat of arms that crowns the main door.

Municipal park:

Formerly in the space where the park is today there was a great depression 3 or 4 metres deep called La Nava. After the Civil War the hollow was filled in with the rubble from the demolished buildings. The current park was built by the Devastated Regions in 1949, and remodelled by the Forest Service of the Provincial Council of Madrid in 1972. On one side of the park are the old schools, now converted into the Hogar del Pensionista.

Potro de herrar:

The livestock crush dates back to the beginning of the 20th century and its original location was in a blacksmith’s shop located in a property close to its current location. It is a characteristic element of agricultural architecture. For much of the 20th century oxen were used to assist in transport or to pull ploughs. For this it was necessary to shoe the animals and this work was done in livestock crushes.

Normally livestock crushes were formed by a structure of four vertical posts that could be made of stone or wood. The animal was placed between these posts. The pillars were joined to each other by wooden beams and from them hung leather girths with which the animal was lifted, held and immobilized. In the front a wooden yoke was placed where the cow was tied. In the upper part of the two rear posts a crossbar was placed to tie the tail. They also had small pillars or trestles with slots where the legs of the animals were secured to shoe them.